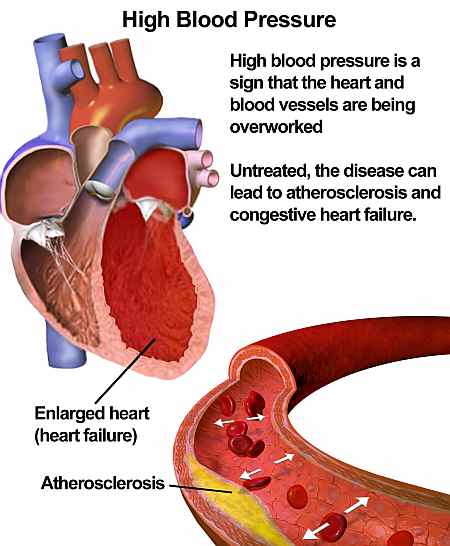

High blood pressure, alias hypertension, is a leading killer. It has no respect for sex, occupation, social status or religion. Cardiovascular diseases account for approximately 50 percent of deaths in this country.

Not only is hypertension one of the leading cardiovascular illnesses, but it is an ancillary hazard of many other illnesses.

People suffering from obesity, heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and a long list of other illnesses are susceptible to high blood pressureand to its complications.

High blood Pressure and Fitness

Although no precise blood pressure reading demarcates normal from high, North American adults at rest may be in for trouble if their blood pressure is consistently higher than 140/90.

Not so with “low blood pressure.” In fact, statistically speaking, persons with “low blood pressure” have a greater life expectancy.

“Low blood pressure” is truly “low” when a person is gravely ill and in shockdue to haemorrhage, severe coronary attack, terminal disease, or serious injury. Many normal people have normally low blood pressure readings.

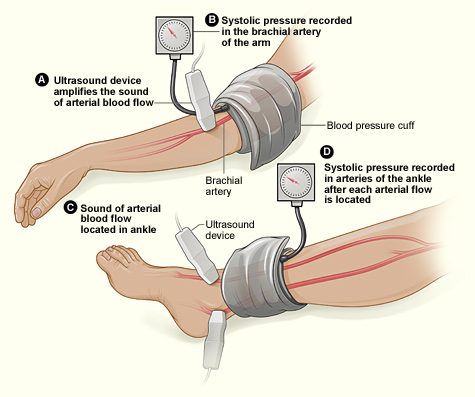

When a physician “reads” blood pressure by means of his “blood pressure cuff” and stethoscope, he arrives at two figures systole (high) and diastole (low).

Thus a normal reading might be 130/80. This indicates that the pressure in the blood vessels is 130 mm. of mercury during the squeezing forward action of blood along the arteries when the heart contracts.

When the heart relaxes and while it is being filled before the next contraction or heartbeat, diastole is said to occur. This relaxed state, or diastole, is 80 mm. of mercury in this case.

Blood pressure, whether normal or high, fluctuates widely during the day and is influenced by normal daily occurrences.

While these rises and dips are transient and almost without clinical significance, they are important as barometers to indicate the adequacy of an individual’s ability to weather the physical and emotional highs and lows which he experiences.

Effect Of Physical Exercise On Blood Pressure

In the untrained subject, a typical or average response of blood pressure during exercise is to riseperhaps reaching a maximum of 200/100 after two or three minutes. And this then might persist for the duration of the exertion.

This is an average change. It signifies a rise in both systole and diastole, but a greater net difference (by subtraction) between the two. This greater net difference indicates that a greater blood flow is being channelled across the muscles, since a larger pressure gradient is being observed.

An increased need for nutrient to the muscles with an increased need to remove unneeded residues of burnt fuels from the muscles makes this seem logical.

The athlete is much more efficient. His blood pressure too increases during exerciseand to about the same “readings”for two to three minutes. Then his diastolic pressure tends to drop precipitously, perhaps to a final combined “reading” of 200/10.

The pressure gradient between systole and diastole is now greatly increased, making for more efficient perfusion of his muscle mass.

An athlete thus does not contract his heart more vigorously (systole), but has educated his heart and arteries to relax more completely (diastole). Exercise has long been known to have a beneficial effect on blood pressure.

The flexibility of the blood vessels during exercise is maximal (high systole and low diastole), with a decreased tendency obviously to “hardening of the arteries.”

The Effect Of Age On Blood Pressure

Although high blood pressure begins at readings over 140/90, this applies only to North American adults. Normal infants have blood pressures of approximately 75/40.

During childhood and adolescence blood pressure gradually rises and it is not until late teens and early twenties that 140/90 becomes the upper limit of normal.

There is a time-honored adage that your blood pressure rises one point per year as you grow older. This is far from true. As the years go by there is a normal tendency toward “hardening of the arteries” (arteriosclerosis). In fact, early evidences of “hardening of the arteries” begin in the twenties and early thirties.

As the arteries become “hardened,” they necessarily lose their elasticity and flexibility.

When the heart contracts, the arteries are less able to “give” or stretch a little, resulting in greater pressure along this more rigid system.

Systolic blood pressure does therefore increase slightly with advancing age. Systole of 140 mm. of mercury at age thirty-five might well rise to 160 at age sixty-five.

But being “hardened,” the arteries are likewise unable to shrink down when the heart is relaxed, or during diastole. Having lost the ability to firm up during diastole, the pressure drops even further.

A normal diastole of 80 mm. of mercury at age thirty-five may become 70 at age sixty-five. Blood pressure is influenced by age. Systole rises slightly and diastole falls.