What if your mind’s eye could take you to a place so peaceful that the experience eased your pain or sped your recovery from surgery? It’s not such a far-fetched concept. In fact there are many studies that show that guided imagery can be good in many parts of your life.

“Guided imagery,” a type of mind-body therapy that uses visualized images to communicate to the housekeeping systems of the body, is making its way into traditional medical settings.

“People are just now taking a very serious look at it,” said David E. Bresler, co-founder of the Academy for Guided Imagery, in Malibu, Calif., and author of the book Free Yourself From Pain. “There are a handful of hospitals around the country and around the world that are starting to implement these programs,” he said.

Studies in Guided Imagery

In one study, researchers at Harvard Medical School found that more than 30 percent of U.S. adults have used some form of mind-body medicine, a category that includes imagery, according to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Bresler, a traditionally trained Ph.D. neuroscientist, first became intrigued with alternative methods of pain relief in the early 1970s, as founder and director of the University of California, Los Angeles, Pain Control Unit.

Patients often used vivid images to describe their pain. It felt like an ice pick to one person, fire ants to another. One particular patient, a psychiatrist with a painful rectal carcinoma, suffered low back pain that he said “felt like a dog chewing on my spine.”

Bresler knew that when patients used their imagination to go to a peaceful place, it helped them to relax, so he guided the agitated psychiatrist through a relaxation exercise. When the man’s pain flared up, Bresler instructed him to speak to the dog. Would it let go of his spine? Then, an astonishing thing happened — when the dog let go to talk, the man’s pain subsided.

Today, guided imagery has numerous applications. Sports psychologists use it to enhance athletes’ physical performance. Cancer centers often use it to relieve patients’ pain and nausea.

In a 2004 study in the journal Pain, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center found that children who used guided-imagery tapes before and after routine surgery had significantly less pain and anxiety than a control group.

More recently, researchers examined how children used these tapes, which suggested that they “go” to a park, at least in their mind. Many, though, put their own spin on the proposed image, allowing them to escape to places like a swimming pool, a lake or an amusement park.

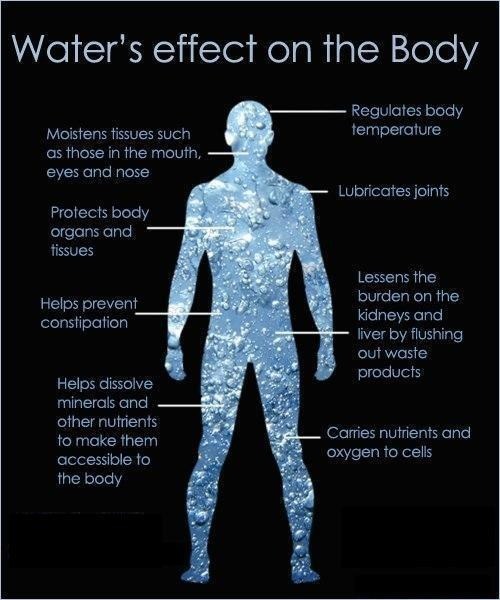

Bresler said imagery is the language of the autonomic nervous system, the part of the nervous system that regulates many involuntary body functions, such as heart rate, blood pressure and digestion. “So, when you’re working with images, it’s really a set of instructions to the system,” he said.

How To Start Using Guided Imagery

Victoria Menzies, an imagery researcher and professor at Florida International University’s School of Nursing, in Miami, said the first step for a patient in any guided-imagery session is to develop a rapport with the guide who is asking you to close your eyes and relax.

Once the patient is in a relaxed state, the guide will either offer an image or ask the person to come up with their own, someplace where he or she would feel calm and safe or joyful — the mountains, the seacoast, a favorite room in their home, whatever.

Engaging the senses is the next step, she explained. The guide might ask where you are and what you see, hear, smell, feel and even taste.

Menzies led a 10-week guided imagery intervention for a small group of patients with fibromyalgia, a condition involving chronic pain and fatigue. In the study, published in January 2006 in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, one group of patients received usual care and used a set of guided-imagery audiotapes.

The other group received only usual care. Compared with the controls, the patients who participated in guided imagery were better able to perform activities of daily living and had a greater sense of being able to manage their pain and other symptoms, the study showed.

What’s more, Menzies found, “The pain did not change, but the ability to cope with the pain was improved.”

Bresler considers it shocking that medical colleagues would reach their hands into someone’s body and remove organs before allowing a patient to go through an imaging exercise.

“It only takes a few moments to do these things and to really check on the wisdom from inside, because there is tremendous wisdom that’s being generated if only we’d listen to it,” he said.